Direction Finding - Astronomical Methods

photo © Emmanuel Salé for openphoto.net CC:NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Topics

Introduction

Astronomical pointers have been the basis of navigation for centuries and can still play a major part in navigation across the globe.

Simple to learn and easy to apply they can prove useful in almost any situation (as long as you can actually see the stars!)

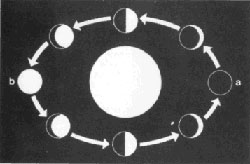

The Moon

The Moon has no light of its own, it reflects that of the sun. As it orbits the Earth over 28 days the shape of the light reflected varies according to its position. When the Moon is on the same side of the Earth as the Sun no light is visible - this is the 'new moon' (a) - then it reflects light froms its apparent right-hand side, from a dradually increasing area as it 'waxes'. At the full moon is it on the opposite side of the Earth from the Sun (b) and then it 'wanes', the reflecting area gradually reducing to a narrow sliver on the apparent left-hand side. This can be used to identify direction.If the Moon rises BEFORE the Sun has set the illuminated side will be on the west.

If the Moon rises AFTER midnight the illuminated side will be in the east. This may seem a little obvious, but it does mean you have the Moon as a rough east-west reference during the night.

The Northern Sky

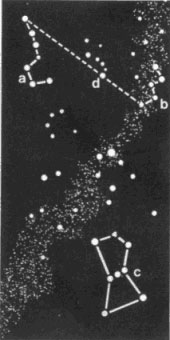

The main constellations to learn are the Plough, also known as the Big Dipper (a), Cassiopeia (b) and Orion (c), all of which, like all stars in the northern sky, apparently circle the pole star (d), but the first two are recognizable groups that do not set.

These constellations come up at different times according to latitude and Orion is most useful if you are near the Equator.

Each can be used in some way to check the position of the pole star, but once you have learned to recognize it you probably will not need to check each time.

A line can be drawn connecting Cassiopeia and the Plough throught the Pole Star. You will notice that the two lowest stars of the Great Bear (as shown here) point almost to the Pole Star. It will help you to find these constellations if you look along the Milky Way, which stretches right across the sky, appearing as a hazy band of millions of stars.

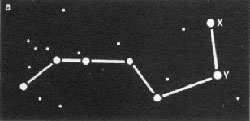

Plough (Big Dipper)

The plough is the central feature of a very large constellation, the Great Bear (Ursa Major). It wheels around the Pole Star. The two stars Dubhe (x) and Merak (y) point, beyond Dubhe, almost exactly to the Pole Star about four times further away than the distance between them

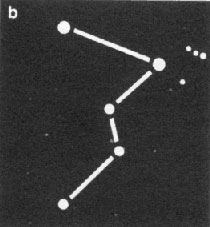

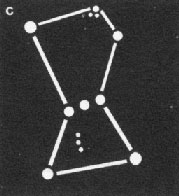

Cassiopeia

Cassiopeia is shaped like a W and also wheels around the North Star. It is on the opposite side of the Pole Star and about the same apparent distance away as the Plough.

On clear, dark nights this constellation may be observed overlaying the Milky Way. It is useful to find this constellation as a guide to the location of the Pole Star, if the Plough is obscured for some reason. The centre star points almost directly towards it.

Orion

Orion rises above the Equator and can be seen in both hemispheres. It rises on its side, due east, irrespective of the observer's latitude, and sets due west. Mintaka (a) is directly above the Equator. Orion appears further awau from the Pole Star than the previous constellations. He is easy to spot by the three stars forming his belt, and the lesser stars forming his sword.

Other Stars

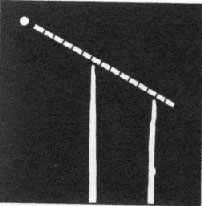

Other stars that rise and set can be used to determine direction. Set two stakes in the ground, one shorter than the other, so that you can sight along them. Looking along them at any star - except the Pole Star - it will appear to move. From the star's apparent movement you can deduce the direction in which you are facing.

- Apparently Rising = facing east

- Apparently falling = facing west

- Looping flatly to the right = facing south

- Looping flatly to the left = facing north

These are only approximate directions but you will find them adequate for navigation. They will be reversed in the Southern Hemisphere.

Southern Sky

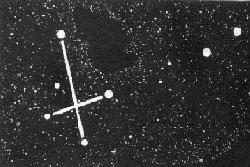

There is no star near the South Celestial Pole bright enough to be easily recognised. Instead a prominent constellation is used as a signpost to south: the Southern Cross (Crux) a constellation of five stars which can be distinquished from two other cross shaped groups by its size - it is smaller - and its two pointer stars.

One way to find the Southern Cross is to look along the Milky Way, the band of millions of distant stars that can be seen running across the sky on a clear night. In the middle of it there is a dark patch where a cloud of dust blocks out the bright star background, known as the Coal Sack. On one side of it is the Southern Cross, on the other the two bright pointer stars.

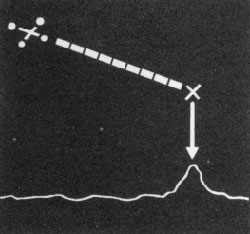

Finding South

To locate south project an imaginary line along the cross and four and a half times longer and then drop it vertically down to the horizon. Fix, if you can, a prominent landmark on the horizon - or drive two sticks into the ground to enable you to remember the position by day.